Subject: volunteer cavalry trooper / raider

Culture: Southern Anglo-American

Setting: Confederate treason, American South 1861-1865

Context (Event Photos, Primary Sources, Secondary Sources, Field Notes)

* Carter 1979 p3-4

"Rich or poor, the youth of the South were born to the saddle and learned to ride in infancy. The hunt, the steeplechase, the gymkhana, or tournament, were the popular diversions. The Southerner conducted his business in the saddle, whether overseeing a plantation, trading in the rural market, or touring the professional circuit as doctor, lawyer, preacher, or government agent.

"[...] [W]hen the war came, the South had instant cavalry material. Tactical training might or might not be imposed, and often wasn't; Southern cavalry rode and maneuvered as later fighter pilots flew -- by the seat of their pants. By contrast, most of the Northern cavalrymen, often arbitrarily assigned to that branch of service, knew horses only by proximity -- 'clerks and tailors on horseback,' training to turn them into accomplished troopers; and, looking ahead, those two years were sufficient. Basically, what the South had was a head start, not a permanent monopoly, not, in the final years of war, even an adequate fighting edge to see them through.

"The Southern equestrian fraternity -- for want of a better term -- developed a rare breed of men akin to the war aces of the air force in more modern times. It was more than riding ability and knowledge of the use and care of horses. It was a sense of being part of the machine -- in this case a four-legged animal machine. ...

"Horsemanship also developed qualities of daring, innovation, and independence in thought and action. A fence or ditch could not be cleared according to studious planning in advance. It could only be cleared with dash; and if that proved insurmountable, another approach would be instantly improvised. The same with facing an unpredictable enemy in this fast-moving fluid means of waging war. Advance orders were of little use; precise goals must depend on opportunities; slate-board strategy was a waste of time when speed and split-second decisions were the ultimate deciding factors."

* Katcher/Embleton 2002 p27

"The highlight of the cavalryman's life was the raid, and it was in raiding that the Confederate cavalry was most used. In the west, cavalry under Forrest, Morgan, and Wheeler struck repeatedly at Union supply lines, forcing Union commanders to make changes in their strategies. Grant had to abandon his attack on Vicksburg from the north, picking a route that would take him south of the city on the Mississippi River, because of a major raid on his supply center at the start of his first try at a campaign there. In the east, Stuart's cavalry entirely encircled the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsular Campaign in 1862, bringing back information to Robert E. Lee that allowed him to begin his Seven Days Campaign that took the pressure off Richmond."

* Bradley 2013 p7

"In December 1862, Confederate cavalry in the western theater mounted a series of raids that, collectively, were the most successful mounted operations of the entire war. Led by Gens. Nathan Bedford Forrest, John Hunt Morgan, Earl Van Dorn, and Joseph Wheeler, the Confederate horsemen demonstrated their ability to engage in a new type of highly mobile warfare. They also demonstrated the potential for this new style of war to disrupt both the tactical and strategic goals of their opponents. In just more than two weeks of active operations, the Confederate cavalry in the West shattered the strategic plans of both the Army of the Mississippi under Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Cumberland under Gen. William S. Rosecrans, forcing these two armies to remain stationary for five months. The cavalry also exercised tactical influence on Rosecrans's forces at the Battle of Stones River by destroying major elements of the supply train of the Army of the Cumberland and by forcing Rosecrans to detach large numbers of troops to guard his tenuous supply line. Neither the Union nor the Confederate cavalries ever matched this unprecedented burst of activity for the remainder of the war."

* Longacre 1986 p23-24

"By mid-1863, the majority of Union and Confederate commanders understood the importance of cavalry power. In the eastern theater of operations, however, only the Confederates seemed able to exploit it. From its inception, the Army of Northern Virginia projected an aggressive role for its horse soldiers, employing them offensively, in mass, and often far afield of the main army. As a result, Major General J. E. B. Stuart's troopers attained a record that far outshone their enemy's.

* Museum of the Confederacy > Between the Battles

"Gone were the days of grand Napoleonic-style cavalry charges -- massed firepower from formed infantry armed with rifled muskets saw to that. Increasingly, the cavalry was used for reconnaissance (scouting ahead of the army to find the enemy's location) and as mounted infantry, traveling quickly from place to place on horseback, then dismounting to fight as infantry, using a shorter version of the infantry rifle called a carbine." ...

Costume

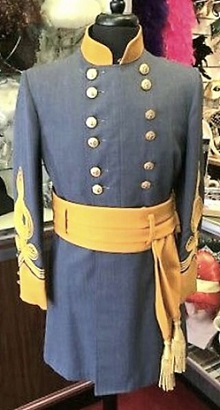

* Katcher/Embleton 2002 p14

"The regulation Confederate cavalryman's uniform included a double-breasted frock coat of gray wool with yellow standing collar and trousers, sky blue trousers with a yellow stripe down each leg for non-commissioned officers and officers, and a copy of the French kEpi with a dark blue band and yellow sides and top. Coats of non-commissioned officers were to be marked with yellow chevrons, points down on each sleeve indicating grade, while officers were to wear gold embroidered rank insignia on each collar; one, two, and three bars for lieutenants and the captain, and one, two, and three stars for the major through colonel. Officers were also to wear gold lace in the form of an Austrian knot on each sleeve, with one lace for lieutenants, two for captains, and three for field-grade officers. The same number of gold bars was to decorate the front, back, side, and tops of the kepis.

"In fact, the uniform described above was little seen in the field, especially the enlisted version. For the first two years of the war men supplied their own uniforms, for which they were paid by the central government, or, in the case of North Carolina and Georgia, they came from state supplies that conformed to state dress regulations. Almost immediately the frock coat was replaced by a waist-length jacket, wiwth a single row of buttons ranging in number from five to nine. By 1863 the central Confederate government took over supplying its troops from a number of clothing depots located around the country. Each depot, as it turned out, had its own unique style of jacket, but most were similar to the short jackets already worn. The system worked well, and, while there were times that Confederates were poorly clad, for the most part they were well and uniformly dressed, although instead of gray wool, the uniforms were more often made of jeans cloth, a mixture of wool and cotton, and colored with logwood dyes that soon faded to brown.

"[...] Cavalrymen were fiercely proud of their branch of service, and many men tried to obtain yellow to trim their otherwise plain gray jackets. Louisiana cavalry Sergeant Edwin Fay wrote home in 1864, 'See if you cannot get me some more yellow trimming for cuffs and collar.' In December 1863 Fay again wrote that, 'We went to Mr. Thigpen's and I took my coats out to have the cuffs and collars trimmed with yellow flannel (Cavalry stripes).'"

* Museum of the Confederacy > Between the Battles

"Though the kepi was called for in the uniform regulations, many soldiers preferred a soft, brimmed hat generically known as a slouch. It proved more comfortable to wear and was much better at keeping the sun out of your eyes and the rain off your neck."

Long Guns

* Wiley 1943 p292

"Among cavalrymen the breech-loading Maynard rifles were held in high esteem because of their accuracy and range. But only a limited number of these could be obtained by Confederates. In the latter part of the war some Spencer and Henry repeating carbines were captured by Rebel horsemen, but these deadly guns -- which, according to one gray-clad wag, contained so many charges that they could be loaded on Sunday and fired all week -- like most of the improved types developed in the North, were of little use because of the difficulty of obtaining metal cartridges.

"Throughout the war Southern cavalrymen used extensively the short Enfield rifle. This was a dependable gun, but, like all muzzle-loaders, cumbersome to load, even when the ramrod was attached on a swivel hinge for convenience of horsemen. Until the very end the short double-barreled shotgun, loaded from the muzzle with buckshot, constituted one of the principal arms of the mounted service."

* Wiley 1943 p297

"[T]here was a widespread indisposition on the part of Rebel horsemen to carry swords of any sort. They chose rather to depend on carbines and pistols, and many doubtless felt more at ease with shotguns than with all other weapons."

Pistol

* Fuller/Steuart 1944/1996 p236

"Next to a good horse, the mounted Confederate soldier wanted most and pinned his highest hopes to 'a pair of Navy sixes,' as the .36 caliber Colt was called. The young Southerner took naturally to the cavalry service. He was accustomed to horses and to firearms from early boyhood. At the outbreak of the War virtually every Southerner wished to enlist in the mounted service. It was a great disappointment to many of them when forced into the infantry.

""While the Confederate cavalryman did a lot of fighting on foot with carbine and rifle, he much preferred to fight astride a good steed, with a 'pair of Navy sixes.' [...]

"The revolver was much more to his liking. The manual was simple -- to draw and open fire. He understood and liked it. That is why when he 'jined the cavalry' his first thought was to get himself a brace of revolvers, Colts preferred."

* Longacre 1986 p34

"It was true that the average Southerner considered his saber more efficacious as a camp tool than as a weapon. While on horseback, he preferred to fight with his revolver; it seemed to answer better in close-quarters fighting and somehow appeared a more polite instrument of death. In battle, Rebels who encountered saber-wielding Federals sometimes shouted: 'Put up your sabres, draw your pistols and fight like gentlemen!'"

* Fuller/Steuart 1944/1996 p254

"The most unusual -- and since the War the most famous -- of all Confederate revolvers was the LeMat, the invention of a Southerner, but the product of a French factory.

"Dr. Jean Alexander Francois LeMat was a Creole physician of New Orleans before the War. Being of a mechanical turn of mind, he was granted a patent by the United States Patent Office under date of October 21, 1856, for his revolving pistol.

"The weapon had a revolving cylinder of .60 caliber for a shot cartridge. This last was fired by a small movable head on the end of the hammer.

"When the War began, Dr. LeMat lost no time in offering his invention to the Confederate Government. About this time LeMat made a connection with the Edward Guatherin Company, of New Orleans, which was engaged in buying tobacco for the French government. The firm began the manufacture of military clothing, the goods being imported from France."

* Fryer 1969 p9-10

"Le Mat Colonel Le Mat was the mid-nineteenth century inventor of the patent revolver which had an extra shot barrel set in the centre of the cylinder. It was made on both the percussion adn breech-loading systems."

* Venner 1996 p47

"[T]he Le Mat is the most renowned of the Yankee [SIC] revolvers. Despite its popularity, only a limited number were actually delivered to Confederate forces (1,200 to the army and 600 to the marines). It fires ten consecutive rounds.

"Its outstanding feature is two barrels: one conventionally rifled .42 caliber serving the nine-shot cylinder, and the other, centered on the cylinder's axis, made for firing buckshot. The two barrels are fired by a single hammer which pivots from one chamber to the other. Those sold to the Confederates were all cap-lock muzzle-loaded models. The inventor of this singular weapon was the French doctor Jean-Alexandre-François Le Mat. Born in 1820, he emigrated to New Orleans after finishing his medical studies and was befriended by Pierre Toutant Beauregard, a future Confederate general."

Saber

* Arms and equipment of the Confederacy 1991 p61

"The hallowed weapon of the great classical warriors, the sword held a romantic appeal for many Confederates. In the Civil War, it served both as a weapon and symbol of rank. In the prewar era, many cavalrymen considered the traditional saber their principal weapon. But since cavalry charges were seldom practical in the overgrown terrain of the eastern United States, nearly all cavalrymen came to rely on pistols and carbines. [...] Staff officers and generals carried swords mainly as a badge of office. (Stonewall Jackson's sword was drawn so seldom that it eventually rusted in its scabbard.)

"Most Confederate swords were variations on U.S. Army models and were made in the South by a number of manufacturers. Many officers, however, wore imported sabers, some carried family heirlooms, and others who had served in the prewar army retained their U.S. swords."

* Wiley 1943 p296-297

"Ordinary Rebs who belonged to the infantry did not carry swords, as these ornaments were reserved to the use of officers. But the saber was an accepted part of any cavalryman's equipment. During the early days of the war, state and Confederate authorities had great difficulty in supplying this type of weapon because of the lack of domestic manufacturing facilities. Caleb Huse shipped several thousand sabers from Europe in 1861 and 1862, and large quantities were obtained by capture and purchase from the North. After 1862, however, Southern firms were able to furnish most of the requisitions.

"The largest sword factory in the South was apparently that of Haiman and Brother of Columbus, Georgia. Clanton's cavalry regiment was armed throughout with sabers made by this firm. A Columbia, South Carolina, establishment turned out an excellent product fashioned after the North's regulation saber. Another Columbia manufacturer made for some of Hampton's cavalry 'long, straight double edged swords, very serviceable and crusader-like with cross hilts.' At Nashville a farm-implements concern reversed the Biblical command and turned plowshares into swords; the brass guards of these high-class weapons bore the appropriate markings 'C.S.A.' and Nashville Plow Works.'

"Other manufacturers were less successful in their efforts to provide serviceable weapons. Swords turned out by Froelich and Esvan, of Wilmington, for the state of North Carolina were said to have been worthless. Cavalry officers complained repeatedly that sabers furnished to their men were of such poor quality that they were thrown away. In this connection, however, it should be noted that there was a widespread indisposition on the part of Rebel horsemen to carry swords of any sort. They chose rather to depend on carbines and pistols, and many doubtless felt more at ease with shotguns than with all other weapons."

* Fuller/Steuart 1944/1996 p236

"The saber was a strange weapon to him. The very fact that he spent so much time making grotesque gestures with it for the edification of the drillmaster gave him a deep-rooted prejudice against it as a weapon. It was all right for a parade or guard mount, perhaps, but he simply could not see its use in a fight."

* Katcher/Embleton 2002 p15

"Southern-made weapons were generally inferior to Northern-made US Army weapons. Southern-made sabers, for example, differed from Southern-made edged weapons, in that the blades were often only single-fullered on either side, the fullers running out at top and bottom, or even flat, which made them weaker than US Army sabers. Blades were often not rolled, but beaten out by hand; as a result they were uneven and of mixed quality. Brass parts were often cast with faults and flaws, and close-fought battles frequently found the Confederates at a disadvantage because of the inferior quality of such weapons."

* Coe/Connolly/Harding/Harris/Larocca/Richardson/North/Spring/Wilkinson 1993 p112-113 (Frederick Wilkinson, "American swords and knives" p104-121)

"The Confederacy was not as fortunate in the matter of edged weapons for, if statistics are to be believed, Union hospitals treated less than 1,000 sword and bayonet wounds throughout the war. This suggests that the Southerners either used their cavalry less or preferred their firearms in action. Many Confederate men and officers were of course still armed with official United States weapons. At the beginning of the war, for example, the Southern cavalry would have carried either the 1840 Heavy Cavalry (Dragoon) Sabre or the 1860 Light Cavalry sword, but as supplies from the North ceased they had to rely on weapons of local manufacture and on imports."

* Longacre 1986 p34

"... Stuart was partial to the saber. He strove to inculcate in his squadrons the value of tempered steel in close combat. Above all, he drove home the lesson that when used on horseback, any firearm delivers ragged accuracy, no matter how near his target."

Knife

* Wiley 1943 p295

"A close observer of doings in Richmond said of the regiments who came to the capital from all parts of the Confederacy in the summer of 1861: 'Every man you met, mounted or footman, carried in his belt the broad, straight, double-edged bowie knife.'"

* Katcher/Embleton 2002 p18

"The one thing most cavalrymen did have, initially at least, was a large knife. Lieutenant R.M. Collins, 15th Texas Cavalry, recalled:

In one thing only were all armed alike, and that was with big knives. These were made for us by the blacksmiths, out of old scythe blades, plowshares, crosscut saws, or anything else that could be had. The blade was from two to three feet in length, and ground as sharp as could be. The scabbards for these great knives were, as a rule, made of raw hide, with the hairy side out, and they were worn on the belt like a sword, and doubtless many trees in the pine forests over in Arkansas show to this day the marks of these knives, for we used to mount our ponies and gallop through pine thickets, cutting the tops from young pine trees, practicing so that we could lift the heads of the Yankees artistically as soon as we could catch up with them.

"These knives proved useless in combat and of limited use in camp, and most were either sent home or sold shortly after the owner entered the service."